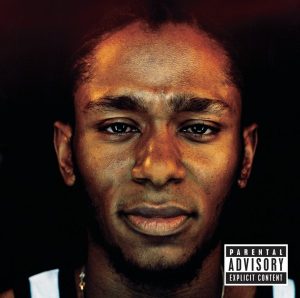

More so than any other genre except jazz, hip-hop’s merits have been built up, brought down, and deconstructed in ways innumerable. This was best verbalized in Mos Def’s “Fear Not of Man,” from his 1999 classic solo debut, Black on Both Sides.

“Listen, people be askin’ me all the time,

‘Yo Mos, what’s gettin’ ready to happen with hip-hop?’

(Where do you think hip-hop is goin’?’)”

One of the stark turnabouts is hip-hop’s current insistence to be mainstream, and the glorification of perceived success. These run contrary to the realities of urban America, and to the origins of hip-hop itself as an inherently outsider culture for those shunned and shut out by mainstream America. Because of the lack of balance that was previously widespread, stratification for rap music is largely nonexistent.

Either you’re talking about guns, women, drugs, or money, or you’re not part of the greater dialogue. You can be “cool,” but by in large, your talk needs to concern the “turn-up.” That’s your finances, how you employ Mac 11s in the alleyway, and/or mistreating “bitches” whenever convenient.

With few exceptions, major record labels are only willing to properly promote negative rap music. To be frank, record companies are using rap music in the same way cartels flood markets with cocaine. The majors take the powder (talent), add baking soda (360 deals, bad or nonexistent A&R, insistence on negativity), and water (the meting of sophistication), then watch it rock up like crack.

“I tell ‘em, ‘You know what’s gonna happen with hip-hop?

Whatever’s happening with us.’

If we smoked out, hip-hop is gonna be smoked out.

If we doin’ alright, hip-hop is gonna be doin’ alright.”

We’re smoked or tripped out, drunk, or “gone off that lean.” Record labels sell this negativity like ice in hell, because the listening audience believes that negativity is black (or brown), and black (or poor) is negativity. Black is cool. Negativity is black is cool.

Young black/brown men in the poorest areas, for the most part, don’t always know if it’s reasonable to think they’re going to make it out, but they can be cool. That’s a harsh, but the numbers provide validity. This packaged rap feels like Eighties-era professional wrestling. Everyone has a part, face or heel, with little room for nuance.

“People talk about hip-hop like it’s some giant

livin’ in the hillside.

Comin’ down to visit the townspeople.

We are hip-hop.

Me, you, everybody – we are hip-hop.”

Black, white, brown, yellow, red, and beyond, if you make it or enjoy it, you are hip-hop. Care for it. Embrace it.

“So hip-hop is goin’ where we goin’.

So the next time you ask yourself where hip-hop is goin’,

Ask yourself, ‘Where am I goin’?’ How am I doin’?’”

As an online columnist, I’m not typically a rear-view person, but during the genre’s so-called golden era, a proliferation of sub-genres existed that’s barely perceptible – or remembered – now. Each group discussed, in its own way, acknowledgement of a similar struggle. Now, we seem intent on not only discarding consistent discussion of issues, we’ve taken it a step further by trying to forget they’re even there, thus the propagation of drug use.

While that’s symptomatic, it’s producing a selective (and seductive) cloud of amnesia. Hip-hop, originally the razor’s edge of urban America and beyond, has reality shows. Actual life turned down for us. (American) rap’s been blunted, both literally and figuratively (for now). In some ways, Desi hip-hop is in position to place itself at the fulcrum of its society's ills, just as hip-hop once did for America's audiences.

“So, if hip-hop is about the people,

And the hip-hop won’t get better until the people get better,

Then how do people get better?

Well, from my understanding, people get better

When they start to understand that, they are valuable.”

And only at that point, and not before.

Credit/previously published here by author