To understand where hip-hop is going, like everything else, we must review where it’s been – and where it hasn’t. The latter refers to the seismic shift in rap and hip-hop that stemmed from the Dec. 17, 1991, ruling on Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc. The case and decision, arguably the most important in music history, changed hip-hop.

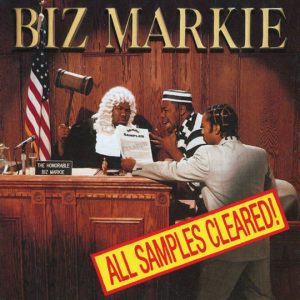

Judge Kevin Thomas Duffy ruled that the use of Gilbert O’Sullivan’s "Alone Again (Naturally)" by Biz Markie was willingly unlawful. “Willingly” remains the critical word, because Duffy hinged the decision on his supposition of purpose in sample use, not whether O’Sullivan actually owned the copyright. The ruling suggested sample use was tantamount to criminal theft, changing (and for some, cementing) the perception of the technique forever.

Where sonically frozen moments in time could be unlocked via SP-1200 or MPC production modules, Duffy essentially halted all near-free use of the material rap was primarily based on. When veteran rap fans claim the genre hasn’t been the same since the “Golden Era,” they’re not being fogies resistant to change. In truth, they’re factually correct... without understanding why.

The decision represented a hard departure for rap, forcing it away from the Mansa Musa-like wealth of breakbeats at everyone’s disposal. Where its production previously represented open frontier in which ideas ran as deep as the producer’s collection, the legal shrinking effectively halted it. This quickly turned beat-making into an increasingly narrow and trend-prone process.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t03PkI5vNl0[/embed]

Interpolation, the replaying of samples that limits payouts only to songwriters, grew as a less costly method to overcome new legal standards. Dr. Dre used the technique to recapture just enough of the original essence on classic albums The Chronic and Snoop Dogg’s 1993 debut, Doggystyle. Yet Dre had been a celebrated producer for nearly a decade already, understanding the nuances of creating hit songs in proper studios and recording budgets.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LK8sxngSWaU[/embed]

The Bomb Squad created “Don’t Believe the Hype” with multiple samples from seven separate tracks, a financial impossibility today. Any rap record from the start of hip-hop through December 17, 1991, was likely made with tens to hundreds of samples. MCs worked with collages of lost or unrecognized artistry to build ideas through individual song structures and themes.

From the late Nineties through today, only artists like Jay Z, Kanye West, and those with unusually talented in-house production teams (like Dungeon Family via Outkast and Top Dawg Entertainment with Kendrick Lamar) have the major label budgets and/or technical skill necessary to craft songs most artists cannot afford because of clearance fees. Then, it became a game of code.

Whereas there used to be considerable sonic differentiation and a need to standout, the production columns are much firmer now than before. There have been many successful producers doing incredible work after 1991, but the legal stoppage created a severing from which we don’t fully realize the pitfalls.

Sampling wasn’t strictly about finding that old Top 10 hit to make a bigger hit, like Hammer’s use of “Superfreak” or Puff Daddy’s flagrant sample use, which bordered on disrespect and tone-deafness. Most songs never hit the Billboard charts, after all. Rather, hip-hop was about discovery and acknowledgement of what came before.

More over, for young urban kids that couldn’t afford real instruments with lessons (much less studio time), sampling from a cheap machine was a way to overcome disadvantage. That MPC and a record player was a way to create a future with the past.

I dare someone to claim that the Rolling Stones rehashing the blues they loved, or Michael Jackson as Jackie Wilson’s reincarnation, is any different than rap producers cutting up breaks in a record they found in a dusty crate. Beatmakers heard the things they loved, and took (or deconstructed) what was available for their own usage in a more exacting and literal context. Perhaps this is the issue.

The takeaway might be that where new music used to involve an obvious and somewhat open appropriation of previous sounds to create something new, now it’s illegal to use music that was never truly original when it was created. If there’s not at least some irony in this, I’m not sure where else you could find it.